If you’ve walked along the banks of the river Thames in central London since the 11th of December, you might, despite the unusually mild weather, have encountered 100 tonnes of glacial ice. 24 ice blocks, ranging from giant, opaque hunks to jagged, translucent shards, are arranged like an ancient stone circle outside Tate Modern and 6 additional blocks are grouped in front of the Bloomberg offices in financial hub of the City. But why have they appeared here?

This is the third part of the Ice Watch series, which first took place in Copenhagen in 2014 and then again in Paris in 2015. The brains behind the project are the artist Olafur Eliasson and the geologist Minik Rosing. The free-floating ice blocks were fished out from the Nuup Kangerlua fjord in Greenland after they began to melt into the sea and transported to London in fridge containers, normally used for frozen prawns. As with Eliasson’s previous public ice-works, Ice Watch London launched to coincide with a global environmental event, this time, the meeting of world leaders at the COP24 Climate Change conference in Katowice, Poland. The duo’s research estimates that every second, 10,000 ice blocks just like these, are dissolving into the ocean and contributing to rising sea levels. Their Ice Watch installation, which is melting away by the minute, aims to highlight the urgency of action against climate change.

Eliasson has said “facts alone are not enough to motivate people; at times, they even create the opposite effect. We need to communicate the fact of climate change to hearts as well as heads, to emotions as well as minds”. And indeed, in cities across Europe Eliasson’s Ice Watch has aroused an almost primal reaction in many of the people who experienced it; a desire to touch, hug, smell, listen and even lick the ice! Of course, this kind of physical interaction is exactly the point of the project. By making abstract facts inescapably tangible, Eliasson hopes that the artwork has the potential to turn climate knowledge into climate action in a way that news bulletins, reports and images can’t.

Eliasson is not alone in his belief in the power of art to inspire radical change. Following a landmark report published by the IPCCin October 2018 warning that we have only 12 years to limit the worst effects of global warming, Nicholas Serota, the Chair of Arts Council England has also spoken about the responsibility of the arts to ‘create a more sustainable future for us all’.

The potential of public art to bring a sense of urgency to the climate conversation has motivated a number of Artichoke’s Lumiere festival commissions, including Consumerist Christmas Tree by Luzinterruptus, made of discarded plastic bags and Daan Roosegaarde’s virtual flood installation,Waterlicht.

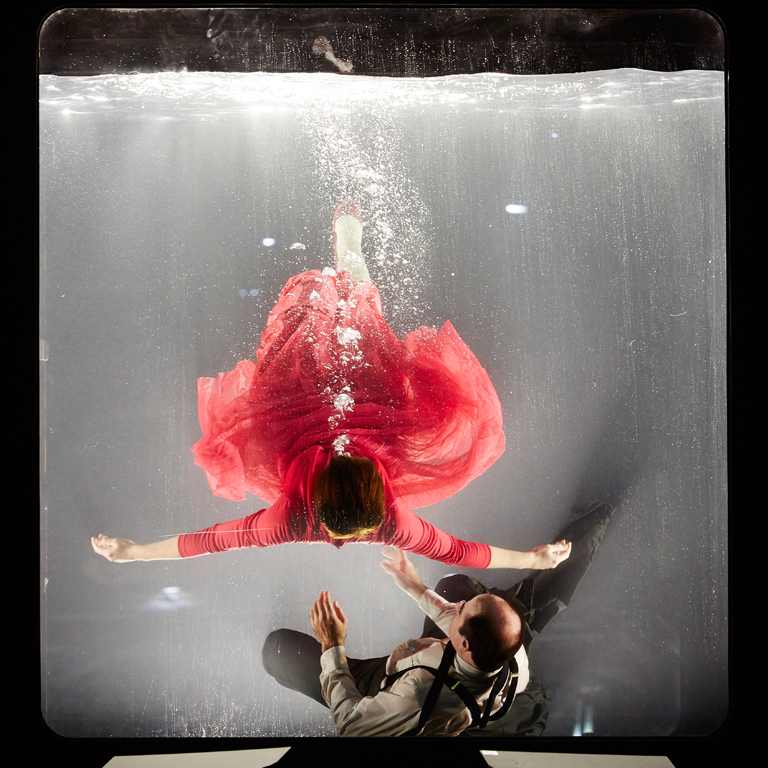

Climate-induced flooding and an increasing fear that some of the world’s major cities could soon be underwater was the focus of Holoscenes, one of the events in the 2016 Artichoke project, London’s Burning marking the 350 years since the Great Fire of London. Holoscenes was a mesmerising 6-hour underwater performance by Early Morning Opera, which examined our fraught relationship with water in the 21st century. In Exchange Square, the giant aquarium filled with 3,500 gallons of water, was the stage for performers within it, blindly continuing everyday tasks like drinking coffee and reading the newspaper. The mesmerising piece made us ask, what will it take to inspire action against climate change? Will we still be treading water in 12 years’ time?

Large scale art with a focus on climate change has also faced harsh criticism. Julie’s Bicycle, the leading global climate change charity working with the Arts Council to support creative projects including Ice Watch, has revealed that one of the first questions directed at Eliasson was: ‘What is the carbon footprint?’. Likewise, the public reaction to our own Instagram post from the Ice Watch launch at Tate Modern ranged drastically from ‘Yessss!!! Let’s shift public opinion by shifting the problem to their doorsteps!!!’ (@cycle_recycle) to ‘This is so contradictory’ (@whoispaigeshetty) and ‘What a waste of energy!’ (@lauwol). The estimated energy cost of creating the artwork is said to be equal to the carbon footprint of one person per ice block flying over to the Arctic and back. In our time of ever-increasing consumption, is Ice Watch irresponsible or is it the eye-opener we need?

Ice Watch London is open to the public on Bankside outside Tate Modern, and in the City of London outside Bloomberg’s European headquarters until Thursday 20th December, or until the ice melts away. Go and see it before it’s gone!

Quotes and facts are provided from the following articles:

Wired: Olafur Eliasson’s Creative Manifesto

The Art Newspaper: Olafur Eliasson’s Latest Work is Melting Away

The Guardian: The arts have a leading role to play in tackling climate change

Julie’s Bicycle: Ice Watch London